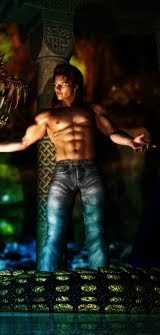

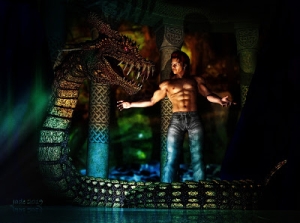

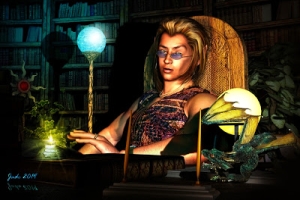

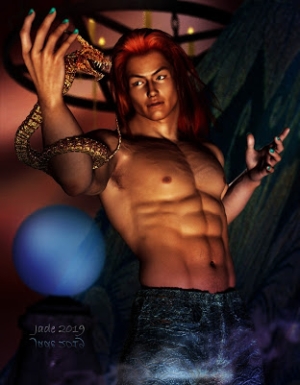

click to see at large size ... makes lovely wallpaper

Chapter Six

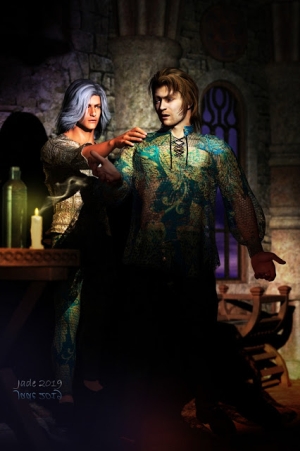

The night hours always seemed to have a way of inviting in ancient ghosts, beckoning them closer, as if they were welcome at the fireside.

A thousand memories returned to Leon while the stars wheeled. They haunted his dreams as he slept in the small hours of the morning, and they were still crouched in the shadows like so many goblins as the first gray light of predawn began to dull the stars in the east.

Some of the memories surprised him, for he had been sure they were forgotten. They came from some dark basement of his mind where they lurked, impossible to completely banish —

Battles he had fought and won, others he had lost. Lands that were so far away, and so strange, he had never grasped the language well enough to know what people were shouting at him as he rode through with the victorious regiment, or dragged his feet through in the company of prisoners.

Dawn pinked the sky with delicate, lovely hues, but that morning he barely noticed its beauty. The sky was brightening over the badlands of Barran’s Heath, where everything he saw reminded him of blood. He had fought his first battle not very far from the old cenotaph.

Not much older than Martin, already a year into his militia service, he trudged out with a hundred others and when noon came around, and the fighting ended, he was one of the lucky ones. The battle was fought out from first light to late morning, and the rocks of this heath ran with blood.

The bandits flew the scarlet and black colors of Macatta clan. They came in from the sea — no one knew where their safe havens lay, but when the black ships were sighted along the craggy coastline between the fishing bay of Krestway in the north and the great trading port of Arkeshan in the south, the call to arms would be heard in every town.

It had been Leon’s choice to stay in Esketh when the Anghari clan moved their wagons eastward for the year. He was fifteen, and his friend had invited him to winter over in Esketh, learn to read and write properly at last, and study with the swordmasters. The Esketh militia masters could teach him nothing about handling horses, dogs, knives, the longbow, but Leon had been watching the swordsmen with fascination for years.

Every spring, the Anghari arrived back at Esketh and stayed till fall, and the summer when he was six years old he met a boy called Roald, when a favorite hound was lost, and a pony lamed, and the weather blew up a storm at the wrong time of the year. Spring to fall, every year, Roald Mendsen and Leon Anghari roved across Esketh’s hills, sailed its craggy shores in cockleshell boats, pored over books in the dusty depths of its library.

Right after the thaw, every year, Roald was always watching for the wagons to come up the road. It was he who taught Leon how to read and write; it was Leon who taught Roald how to expertly handle horses and hounds, throw knives and draw a bow longer than he was tall. They learned the skills of the sword, lance and crossbow together, for the Gypsies had no such tradition.

But every night at early twilight the curfew bell would chime, and Roald scurried back to the city gates. Those underage, and older men who who had refused to do militia service, had to be back in the safe custody of the Esketh Guard before full night fell. It was the law — and it was a wise law, Leon had seen at once, since the badlands were damned dangerous at night. Ex-militiamen had had the training, they could take care of themselves, while those who spurned the militia were held under suspicion.

But as a Gypsy, Leon never answered the curfew bell. He was an Anghari, beyond the laws of the city, and he always waved goodnight to Roald as the tall gates closed over. The Gypsy nights were alive with revels. He sat at the feet of his uncles and elder cousins, learning the old stories and songs, watching as the conjurers practiced, betting on the knife throwing and ale quaffing contests. And always he would frown at the city walls and wonder what the evenings were like inside Esketh.

One night, when they were twelve years old, Roald invited him to stay in the Mendsen house, and Leon was quick to agree. He washed and put on clean clothes at the insistence of his great aunt. Miranda had sworn to his mother that she would teach young Leon all the proper manners, so he would not disgrace the Anghari before the rich folk of Esketh and a dozen other towns between there and Setzele, which was the clan’s wintering ground.

Scrubbed clean and wearing fresh silk and his best polished leathers, the twelve year old Leon dined at a table for the first time; sat in a drawing room and listened to a quartet of musicians performing music that sounded strange and enchanting to his ears. He had never heard the viol, the harp, the flute and the bodhran played in concert; nor had he ever heard such melody and harmony. The Gypsy music was wild and free; the music of Esketh was like the rest of the city — civilized and restrained.

After dinner, he listened to the stories of business, fishing boats, trade, told my Roald’s parents, and he gave a thought to his own parents, who remained in Setzele all year around now. They were too old for the road. They were already getting quite old when Leon was born, for he was the last of a tribe of children, and unexpected. He was twelve, when he first dined at a table and listened to civilized music. He was poised on the very brink of manhood, as it was understood by the Gypsies. The Anghari came of age at fourteen years.

Among the folk of Esketh, Roald, who was just a few months older than Leon, was still regarded as a youth. He would continue to be a youth until the age of seventeen, when he could begin his militia service at his own convenience, so long as he moved into the barracks before his nineteenth birthday. When he completed his militia service, he would walk away from the barracks with full majority, and every privilege of an Esketh freeman.

Even at twelve, Roald was resigned to it. He was more of a man than his parents gave him credit for. He knew the way Esketh worked, and what his place in the machine must be. Many young men did not come back from militia. They would fight many battles in their years of service, and the field of grave markers on the north side of the city was wide, and always growing. Roald knew this and was resigned to it, as his father and uncles had been.

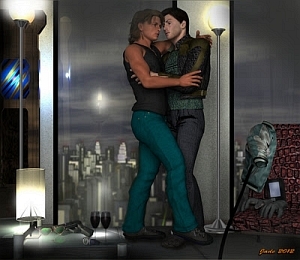

Long after dinner, when the older folk had drifted out onto the patio with wine and the musicians were playing much more softly, Roald led the way to the long bedroom with the screened windows, on the house’s upper level. The view of the gardens would have inspired a painting, and the air smelt of jasmine and neroli, from the trees growing right below the windows. Just as the boys had traded information and skills about horses, hounds, and the arts of reading and writing, they explored the curious, complex art of lovemaking, discovering for themselves how it worked, and worked best…

That year, Leon began to drift away from the Anghari, began to drift toward Esketh, where the cool green gardens were havens of peace and quiet, the library was a treasure house of knowledge he could never have imagined before, and where nights spent in Roald Mendsen’s company were filled with pleasure and affection.

Night birds called out of the badlands, returning him to the present with a start, and he blinked his eyes clear, surprised to see the sky was pink, mauve, with streamers of gold like eagles’ wings that seemed to map out the route of the spice road which ran north and south through the mountains.

Ancient cities drowsed there, at the heart of the old kingdoms. Esketh lay at the center of the kingdom of Rasanu, but it was not the oldest of the sovereign lands. Every year brought threat in the form of raiders, clans like the Macattas, and for Esketh to survive long enough to claim the dignity of being one of the most ancient lands, it must continue to fight hard, as it always had.

The thought took Leon’s eyes back to Martin. He seemed to have spent half the night watching the youth sleep — and wondering where his own life had vanished to. It seemed like yesterday that he had made the decision to stay in Esketh, where he was welcome in the Mendsen house, and Roald’s father had offered to teach him how to handle a boat much larger than the little cockleshells he and Roald had played in for years.

If Leon stayed, Roald warned, he would become subject to Esketh’s laws. Only Leon’s standing as one of the Anghari gave him the freedom to come and go from the city as he pleased at any time of the night, ignoring the curfew. If he stayed, he would be inside the city gates before nightfall, and he would be expected to offer himself to the militia for the full term of service in return for full rights and privileges as a an Esketh freeman.

The badlands by night held no dread for Leon. The Gypsies had no quarrel with the brigands who ravaged their way through cities like Esketh and pillaged places as grand as Arkeshan. He had been riding horses and handling dogs and hawks since he was a child, and he had already learned the arts of the sword from the very masters hired by Roald’s parents to teach their son as a gentleman’s heir should be taught.

He was tall for his age, big, strong, as his father and uncles had been. He had no fear of the militia, and he had come to respect Esketh, and to see that it should be defended. He and Roald went to the barracks together. For them, the training was easy. The few skills they still needed to learn came naturally, the routine was not especially demanding, and they kept their own company.

Not until the black ships came, bringing the Macatta into Esketh’s waters, and blood into Barran’s Heath, did the life challenge either of them, and by noon on the day of their first battle, they were both injured.

The raucous noise of squabbling crows drew Leon back to the present. As dawn flooded the sky, he turned his left arm to see the side and back of it. He wore a long silver scar there, and would carry it for life. The wound was dealt by the tip of a great spear, and if he had been a fraction of a second faster he would have slithered out of its way. But by midmorning he had been on the battlefield for hours and fatigue had dug its cat claws into him. Young though he was, he had begun to tire, and he was slow enough for the spear point to rake him from shoulder blade to elbow.

It opened his skin, but the wound was shallow — muscle and sinew were safe. The militia surgeon doused it in alcohol, inspiring a roar from Leon such as the scourger had never dragged out of him, and then stitched it up with gut and bandaged it with salt.

Roald was not so lucky. His wound was in the side, under the ribs, and he had turned a sickly shade of green as he lay in a wagon, waiting to be taken back to Esketh. The surgeon had packed the gash with herbs and salts and strapped bandages tightly around him, but until he could open the cut up wide, look inside and see what damage had been done, Roald lay in the lap of the gods.

The wagon carried four other young men who were in worse shape than Roald. There was no space for Leon, so he clung dizzily to a saddle, riding beside the vehicle, since he could no longer use his left arm well enough to be any use in the battle.

They both lived, that day. They left the battlefield much wiser than they had entered it, much less cocky, and Leon’s memories were seared into his brain. He knew he had coped with the fighting better than Roald had, perhaps because he was an Anghari, and used to the hunt, the kill, the hard life of the road, while Roald had grown up in a fine house, with young parents who loved him and servants to do the heavy work.

Perhaps this was the reason Roald left behind the soldiering life as soon as he was free to walk away from the militia. With the rights and privileges of his majority, he joined his parents and sisters in the family’s business, and he offered Roald work among the fishing boats.

But as Leon walked away from the barracks for the last time he saw the blue and white banners of Arkeshan fluttering beside the city gates … he heard the drums beating a call to arms for professional soldiers, saw the gold coins being offered — ten gold coins for any man with the skill and the nerve to go to the rescue of the old city, which was beset by raiders from the sea.

A few weeks, said the officer in command of the recruiting party. A young man, blond and blue eyed, with a nose full of freckles, who wore a polished helmet with a great blue hackle. He opened a velvet pouch stuffed with gold coins that rolled out across the ivory-white surface of the drum. A month at the longest, he promised — the relief of Arkeshan could take no longer than this. Who would fight for Arkeshan, for pay? Ten gold coins was a fine fee for a few weeks’ work.

The look in Roald’s eyes was dark as Leon showed him the single coin he had taken as a downpayment for his services, when he signed his name to the contract. The sergeant at arms had given him a pen and said, “Make your mark, son,” but Leon could write. Leon could have told him the history of his own city through the last hundred years — he had read the big green-bound book in the library, while the winter snows kept young men like himself and Roald prisoner in Esketh.

Roald had not wanted him to go to Arkeshan, but the gold was warm in Leon’s palm. He liked the feel of it. He wanted more of it. And a job working on the fishing boats would pay him in copper at first, later in silver. Never in gold. Never enough for him to walk into Esketh with a high head, buy a house like the Mendsen property.

The truth was, Roald knew Leon must go to Arkeshan, and why. His disapproval and doubt were made with a single dark look, not with words. He never said a syllable to Leon about the decision, and when Leon returned — eight weeks later after a campaign that had taken much longer than anticipated, with a heavy purse and not a mark on him to show for the victory — he asked his father to take six of the gold coins and invest them for Leon.

Four months after the relief of Arkeshan, a lieutenant from a regiment of professional soldiers commanded by Luc Chalmera came to find Leon. At the gates of Esketh, he asked for Leon Anghari by name, and Roald’s eyes widened, as he learned how Leon had distinguished himself in the campaign. Leon had said nothing, since it would only have sounded like bragging. Luc Chalmera was offering him the rank of sergeant, in command of a company of his own. Ten men who would fight with him, under his authority.

The pay was forty gold coins plus a calculated share in any spoils of war, in exchange for six months of Leon’s life … six months on the road, fighting for the freedom of the trading city of Thulis, which was under siege. A rider had escaped, bringing out the duke’s pledge of rich pay and high honors, for any professional soldier with the courage and skill to fight for Thulis.

And after Thulis it was Krestway, then Tenereth — always further and further from home, as Chalmera’s regiment was hired by another city in desperate need. Where the years had fled to, Leon did not know. Time seemed to trickle away like storm water in the desert.

Twice in any year, he would meet Roald, when a letter had somehow made it through to Esketh, and they could contrive to be in the same town at the same time. Roald would bring news of the family, and Leon grieved with him when his parents died, celebrated with him when he became engaged to Imara, and then married. Always, after dinner and wine and lovemaking in the best room in the best tavern, he would give Roald a purse of coins to be invested … always, Roald would look at him with dark, brooding eyes and want to know when Leon was coming home.

Home? The word taunted him. He had wondered for years now, if he even had a home. How was it possible for a Gypsy to have a home? Chalmera’s company knew him as Leon Anghari, as if ‘Anghari’ were his name. Leon knew better. The Anghari were a big, rambling clan, a loose association of families who traveled together, trading between Setzele and Esketh, and any point along the way could be called their home.

His parents had died in Setzele five years before, on the morning he watched the dawn blush the sky east of the old cenotaph. His siblings and cousins were scattered along every part of the road back there. And Leon had not slept a single night in Esketh in eight long years.

Too long, he thought as he began to stir himself. Much too long. Roald’s parents were dead now, too. The Mendsen house was Roald’s own, and the accounting books made pleasant reading. Leon had ridden away as a common soldier with a small investment made on his behalf. Fourteen years later, he was reasonably wealthy — wealthy enough not to have to solider any longer, if he chose not to; and the truth was, he had been ready to make that decision for a long time.

Esketh had called to him like a siren for two years and more. He had longed to return, and last afternoon, when he rode up to Road’s gate, it was a warm welcome and a homecoming feast he had expected, not a face filled with worry and a desperate plea. ‘Leon, will you go out and find him? Find him before the skinners can get their hands on him!’

Not merely Roald wore that worry-bruised face. Imara wore it too. Leon had not seen her in years, but he liked the way she had matured from girl into woman. According to Martin, there were four little ones now. There had only been two, the last time Leon spoke to Roald — which only assured him that he had been gone for far too long.

Daylight was bright enough now to permit travel, and time was wasting. With an effort he stirred and shook Martin awake with the toe of one boot. The lad was flat on his back in the warmth by the hearth, which still glowed with the last heat of the night’s fire. He had slept soundly, and would probably sleep till the sun was high, if he was allowed.

The night would have exhausted him, with the healthy fear of Yussan and the chaotic emotion as he awoke to his sins and paid the price for them. The flat of Leon’s hand on his rump was not the price. Leon knew exactly how hard he had hit Martin, and it was less than a tickle by comparison with the birchings meted out any morning in the militia. But the tanning had inspired Martin to discover remorse; and the pain of true remorse was keen, deep, and lasted far longer than the transitory smart of a tanned backside.

Martin had been raised in a wealthy man’s house where life had been so easy, he had little concept of hardship. He looked very young in sleep, but youth was an illusion. The Anghari had regarded Leon as a man since his fourteenth birthday. The city of Esketh would still refer to Martin as a ‘youth’ because he had refused to serve the militia, but Martin was a man — and a beautiful one, as Yussan had swiftly seen. No wonder Martin wanted nothing to do with the militia, Leon thought as he got to his feet and used his toe to stir the youth a second time.

“Come on, kid,” he said gruffly. “Martin! Time to move. Daybreak. Time’s wasting and we have a long way to go. I want to get you back where you belong.”

He jerked awake with a shock, more than likely wrenching out of some dream. He sat up too fast, dark hair in his face, blue eyes still full of sleep. “Huh — where am … oh.” Memory raced back fast enough, and he blinked up at Leon. His cheeks flushed in memory, but he gathered his wits quickly, recovering some modicum of dignity. “Is there anything to eat? I’m hungry.”

Kids his age were always hungry. Leon remembered years of being permanently famished. One good thing about the militia, they kept the food coming, and when a young man held out a pate, it came back loaded. The memory made him chuckle. “There’s some jerky left,” he told Martin. “We’ll eat on the road.” He was moving as he spoke. “I’m going to saddle the horse. Move it, Martin. Put out the fire and pack up here — make yourself useful.” Martin was yawning and stretching, looking so much like a big, pampered cat that Leon hid a smile. “We’ll be back at Roald’s house around noon. I’ll talk to the sheriff, when he shows his ugly face.”

“Thank you.” Martin heaved an enormous sigh, as if the scenes he was racing toward had just begun to dawn on him. “But … you know I can’t stay in the city.” He was on his knees now, and looking up at Leon out of wide, troubled eyes. “I have to make something of my life. You said you understood.”

“I do understand.” Leon paused, hands riding his hips. “But if you refuse militia service your options don’t extend very far. You know that much as well as I do.”

“It’s why I can’t stay in this city,” Martin said darkly. “There’s nothing for me here. Roald’s been seeing it for years, I’m sure.”

The observation was keen, and Leon mulled it over for some time, watching the geese skeining across the distant mountains, on their way to the breeding grounds near Thulis. “Maybe he has,” he admitted. “He was out of his head, worried about you, when I rode up to his gate yesterday … but not surprised you’d taken off. Like he’s been expecting something like this.”

Martin stirred restlessly. “You’ll be gone soon, won’t you?”

“Perhaps.” Leon was far from certain where the future lay. Much depended on those account books, what Roald had to tell him, when they talked over the results of the years of investment.

“When you leave,” Martin whispered, “take me with you.”

The words did not quite astonish Leon. “You know what I am, kid. I’m a mercenary. You know what that means? It means I drag my boots from one battleground to another, fighting someone else’s wars. If you don’t want to do militia service, why would you want to attach yourself to me?”

With what seemed an enormous effort, Martin hauled himself to his feet. He was not as tall as Leon, and he was slender, supple. “But don’t you need an apprentice or … something?”

Groaning, Leon took him by both shoulders, resisting the impulse to give him a little shake. “Apprentices sign on to learn a trade. What would you be learning, if not soldiering? That’s the trade I know, Martin. You already said the life isn’t for you — so you landed here, looking for a guide to treasure, wound up caught by my cousin, and … tanned.” He shook his head slowly. “Pack up. I’ll see to the horse and find the jerky.”

The look on Martin’s face was one of exquisite confusion, betraying a dark chaos of thoughts. In fact, Leon’s heart went out to him. He knew the kid could not stay much longer in Esketh. In fact, Martin should probably have left months ago. He did not want the life of a militiaman, and that was fair enough; but the life of a solider of fortune was little better.

Sighing, Leon swung down the steps and went around into the early morning shadows to attend to the horse. Martin should have been packing, but trailed after him, watching as he fed and watered the vanner, and sorted harness. Leon wondered if he knew how lucky he was to get out of the episode with a lightly tanned backside. Martin was far from stupid, but seemed to have a poor grasp on realities — as if Roald had sheltered him too closely, spoiled him just a little too much, as one would, for the adopted orphan.

The future must be mocking him now, as the morning brightened, Leon thought. The scene had been a disaster, and he must be dreading having to face Roald, much less run the gauntlet of the Esketh Guard, not to mention the sheriff. But at least Martin fully realized the position he had put Roald in now, and from the stricken expression on the lovely face, Leon was quite sure he bore only great affection for his guardian.

Yet the truth was still the truth, and Martin had known it for months or years. There was no future for him in the city. He must leave, and soon. Confusion tormented him, and Leon wished he knew of some magic to set affairs right for him.

But if the sorcery existed, Leon Anghari had no knowledge of it.

NOTE: The Abraxas Contents List is in the left-side column -- quick links to each chapter

NOTE: The Abraxas Contents List is in the left-side column -- quick links to each chapter

********************************************

It was fun writing this chapter because there's a lot of new material in it. A lot of the backstory of Leon and Roald has landed in this chapter -- it was impossible to do this in the graphic novel version. This whole story was going to be told, in the web comic, in a combination of vivid, evocative full-plate renders backing the characters who would stand in the foreground reminiscing. It actually works a lot better this way.

October is racing by ... it's only a week till Halloween, and I still need to dust the cobwebs off The Vampire Amadeus and his bratty human sidekick/boyfriend, and render up something memorable for the end of the month! Note to self: pull the finger out and get busy.

And as I was putting the signature on today's art I realized how few times I'm going to be signing anything "2012" after this. It's going to be 2013 before you know it. Dave and I are already planning the Christmas brunch! (If you follow his blog or twitter, you'll soon be seeing the plans, and then the actual spread. We do this every year: forget dinner ... you end up too full after nibbling all morning on the brunch.)

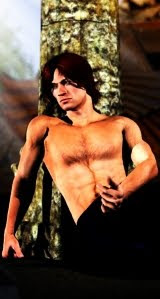

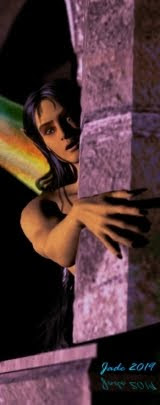

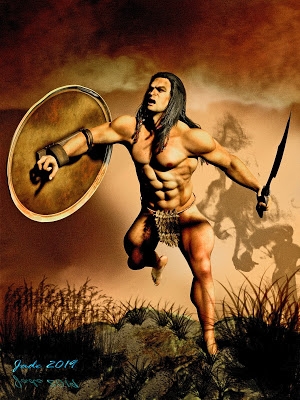

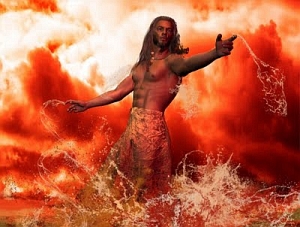

Today's art is deceptively simple. It actually took about two days, including a loooong render and a lot of painting. I'm very pleased with this one. The sky wad extensively painted in Photoshop after being designed and rendered in Bryce 7 Pro. The hair is about 70% hand painted, while about 60% of the shadows and 90% of the highlights on everything are painted. The result is so nice -- and at 1600 pixels wide, it makes a great wallpaper, if you like fantasy guys as much as I do. Enjoy.

Back soon -- hopefully before Halloween! -- with goodies; and then at Halloween it's the Vampire and his beau, with a new set, props and costumes. It'll be fun.

Jade, October 23