Chapter One

Barran’s Heath stretched north and south into the blue distance, misty under the light of the full moon. A dozen miles away in the east was the ancient port city of Esketh, and much further, over the dragon-back of the Blue Mountains in the north, was Arkeshan itself — renowned as the ‘city of silk and sin.’ Closer at hand, the heath was a harsh place of bare rocks and ruins that might have been the bones of great animals that had died here millennia ago and were weathering out of the thin turf.

This place had a bad reputation. Bandits ranged here, striking out of mountain lairs — the old folk spoke of rogue sorcerers who could command terrible demons, and even Martin knew about the slave traders who worked the trails that snaked like serpents through the badlands.

Few people who ventured out on Barran’s Heath by night were anything less than bad company — Martin knew the risks. He had always known. Six hours before he had chosen to accept them, but the sunny afternoon, the noise and excitement of the marketplace, the smell of spice and incense, seemed a thousand years ago now … and after dark Barran’s Heath was the last place he wanted to be.

It was still daylight when he found his way into the strange, wind-sculpted ruins. People said they were ten thousand years old. Martin knew nothing of their history, only that they felt haunted, and he wished he was far away.

Waiting there for hours, he had watched the sunset and the twilight gather, as daylight spent itself. The early evening had been glorious, and now the stars would have seduced any astrologer from the marketplace, any astronomer from the royal court of Arkeshan. But as daylight faded into the myriad tones of blue and mauve and indigo, wolves began to howl. Now, mist gathered in the lowlands, where spiny trees somehow clung to life and the ancient ruins took on the appearance of bleached bones.

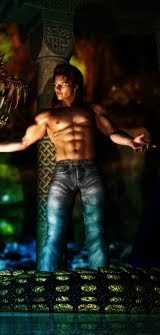

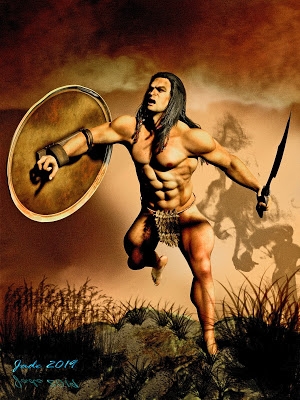

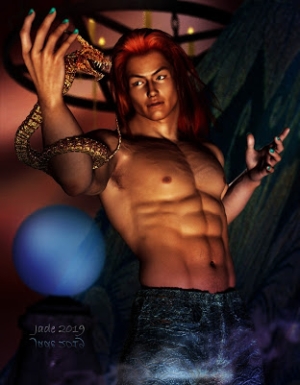

His pulse was fast and his skin prickled with sweat though the night air was chill. He wished he had dressed more warmly, but he had come here direct from the market, when the afternoon sun was too hot for comfort. Like most young men his age, he wore a wrap about his hips, boots that could have used a lick of polish, and a hooded cloak which was more useful to protect him from the burn of the sun than the icy fingers of the night’s growing chill.

Little scuttling sounds issued from the ruins, and gooseflesh rose along his limbs. It could only be rodents and small reptiles, he knew. They came out to hunt in the hour after sundown, and they were harmless. But Martin had begun to jump at every sound as he waited there, and when he heard the scatter of pebbles, the rasp of boots on the rocks, he was on his feet in one lithe movement, straining to see in the blue darkness.

His voice sounded light and thin. “Hello? Is — is that you? Is that Aelmed? She — she told me you’d be here before sundown.” There was no answer from the deep purple shadows, and his heart hammered on his ribs. “Hello? Is there someone there?” Or was he just imagining the sound of boots on the rocks, and it was only the nocturnal hunters?

What a fool he had been! Martin cursed himself now, for he could see the truth of it. He had no one but himself to blame for the situation, and a small voice in the back of his mind whispered, over and over, he could so easily pay for his foolishness with his life.

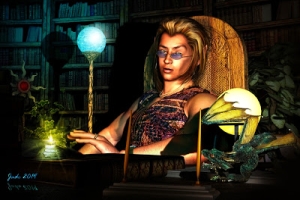

He hunkered back down on the rocks, where the last faint trace of the sun’s warmth endured, and pulled the hood up about the wind-tangled mass of his hair. He wrapped his arms about his chest and tried to huddle into the cloak as he chastised himself for an idiot —

Yet, even then his memory took him back to the afternoon in the marketplace, and he knew he would always have done this. No one forced him to come out onto Barran’s Heath, and the fact was, he would do it again, if some magician were to roll back time and give him the chance to go back and live the day trough again.

It was a wild goose chase, he thought feverishly — and he, himself, was the goose! The man he had arranged to meet at these old ruins had never shown his face before sundown, and since night had already unrolled across the heath like a funeral shroud, this Aelmed was unlikely to appear before dawn.

It was the fool’s mistake, and Martin knew it — yet at least he had a reason for heading out into the badlands late in the afternoon. Other young men who ventured out here were usually doing it as a dare. On their return to Esketh, they would answer to the Sheriff for the crime of being outside the city walls after curfew. It was a dozen lashes of a stout cane for them. A dozen stripes across the buttocks and a sound lecture.

But Martin had his reasons, and they had seemed good enough to the time. Now, as the shadows pooled like black ink around the eerie shapes of the ruins, he was far from sure how good they were, and his blood cooled as he listened to the wolves and jackals which came out to prey as night fell.

The danger was very real, and he wondered at his own sanity as he admitted to himself, mad or not, he would do it again — because the stakes were as high as the risks.

His memories revolved around the old gypsy woman, with her headscarf the color of bright new blood, and her eyes, dark as obsidian, hinting at things she had seen, and knew, that were beyond Martin’s imagination. Many afternoons when he was not studying, he went to the marketplace to watch the dancers. The gypsy girls and boys were the best dancers, and the most beautiful, in this country — or any country. They danced in wisps of silk and strands of gold and polished stones, tantalizingly near-naked in the shadows of market stalls selling the wares of a dozen near kingdoms through which they traveled and traded from the mountains to the ocean.

But that afternoon Martin soon lost interest in the dancers. By chance, he heard a few words of the story old Miranda was telling, and the dancers seemed to fade away like joss smoke on the breeze. She watched him fetch out a silver coin; she took it from him in payment, to tell the rest of the story, and he sat at her feet, rapt, till she was done.

“’Tis an old, old story,” she swore, “and well known in the cities in the north, where travelers tell of a place in the hills, a high valley known only to a handful of men whose courage took them there. A place where treasures beyond value remain hidden …”

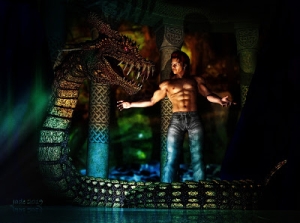

And the most precious of them all was a wyrd compass which turned not toward the north star, but toward magic. It pointed to any magic, but the siren song it liked the best was the ancient sorcery of the enchanted isles.

“You wouldn’t make a fool of me, would you?” Martin asked when she paused for a draught of ale to ease a throat grown dry with storytelling. “You wouldn’t tell a boy tall tales, and send him out on a wild goose chase, would you?”

But Miranda only laughed, deep and husky. “Be assured, lad,” she told him, “the story is true, every word of it — and a lot more I’ve not spoken to thee.”

“Then, there’s really a valley …?”

“A valley,” she affirmed, “where the high slopes glisten year-round with snow and the depths live in shadow so deep, the sun shines there only once in a year. And on the slopes of the valley stands a tomb — lost now, lost in time. Only a few adventurers know where it is, and they’ve grown old, white-haired and toothless with the years. Still, for a price, they’ll take you there.”

“For a price?” Martin was reaching for the purse that hung on his girdle.

“A gold coin.” Miranda shrugged. “They see the trip as a terrible folly, but they’ll do it, if someone has a gold coin to risk on it. And if you go to the old ruins when the shadows grow long, you’ll meet a man who knows the way. He’s there every day at sundown, servicing his traps. In his youth he was an adventurer, and now he lives in the badlands, catching mink in the summer, ermine in winter.”

“This man, you know him, you trust him?” Martin hung on ever word. He knew the way to the ruins. He had seen them many times, when he was out shooting rabbits for the kitchen pot.

“His name is Aelmed,”Miranda said easily, as if it were no matter.

And her attention was already elsewhere as her granddaughters called her name. They were trading glass beads, earthen pots, chickens, and when the haggling went on too long it was always the wise old heads who came to decide a fair price at last.

The dream of treasure was seductive. Martin had tarried in the marketplace, at war with himself — wondering if he should go home and talk it over with his guardian. But he knew what Roald would say. He would believe not a syllable the gypsy had said; he would tell Martin to enjoy the summer afternoons as long as he could, for in a few weeks classes would resume, and he would be back to the feet of his tutors, studying the trade of the scribe.

Roald had served his time in the militia — he owned his home, he ran his business, he loved his wife, and he could have no inkling how stultifying the life of a scribe could be. He had nothing to gain from following the dream of treasure and adventure out onto Barran’s Hearth … but Martin had every reason to be here —

Even though he had begun to think old Miranda might have been preying on his gullibility. Did she send him out here to literally pass him into the hunting nets of the bandits who thronged these hills? But Martin was reluctant to believe it. He knew her as a wonderful old woman who had been an elder among the gypsies for as long as he could remember. Everyone loved her. Surely, she would never work hand in glove with bandits and slavers.

Yet a second time his heart jumped into his mouth, for the scuffling sounds he had been hearing among the ruins had indeed become footsteps, and he knew they were coming closer.

He was in trouble, and he was wise enough to realize it. Not even the lure of the enchanted isles was worth the agony of fear that raced through him as he got carefully to his feet. The old woman’s story was still in his ears, taunting him — one word haunted him, he heard it over and over. Atlantis.

Mariners swore the most enchanted isle of all was marked by a great bronze pillar in the sea, from which the magicks called out strongly. The man who owned the wyrd compass — which Miranda swore was hidden in that temple, in the lost valley — would find his way to the pillar; and the gold-clad land of Atlantis lay just beyond.

This was the dream that had brought Martin into these blasted hills, and it taunted him even as his eyes widened to peer into the darkness, trying to see the figure who was approaching from the tangle of the ruins. He would come here again, against every voice of reason —

The question was, would he live long enough to see the moon rise tonight?

His heart hammered against his ribs as he stood, lifted his chin, and called hopefully,

“Is that Aelmed? The old woman said you’d be here before sundown. You’re late tonight, but I — I have a gold coin for you, if you’ll be my guide.”

NOTE: The Abraxas Contents List is linked from the left-side column -- quick links to each chapter