Chapter Five

The night was calm, and not really cold at all. As fear dwindled, Martin realized that most of his chill had been the result of sheer dread, while the late summer evening was actually clement, pleasant. The sky was a vast, deep blue inverted bowl, with the last traces of the sunset that would linger for an hour yet, and an ocean of stars.

On any other evening, he would have said it was a glorious night for a ride, and if someone like Leon had taken him outside the walls of Esketh after curfew, Martin would have been breaking no laws. Tonight, he saw the same stars, felt the same soft breeze on his face, but he could feel Leon’s anger in the stiffness of his spine, and he knew the reckoning was coming.

Soon enough, he saw the old cenotaph in the distance, where the badlands gave way to high pastures. Goats and sheep grazed there, and trees began to overcome the thorn bushes and stones. Bats called out of the darkness as the gypsy horse approached, and Leon knew these trails. He took the horse by the shortest rout, and drew rein under the weathered marble steps.

The cenotaph was as old as Esketh. It was built to commemorate a battle fought here, where thousands died in a single day. Martin knew the story but had never known if it were truth or legend. No one was quite sure, since it happened long before the earliest memories of the grandparents of even the oldest people alive today.

Ivy had overgrown the building now, and the marble was cracked. Still, it offered a ready-made shelter, and Martin knew without asking, Leon had used it before. As the horse stopped, he slid down out of the saddle and looked up at the warrior.

“How come you know me? I don’t know you,” he said honestly.”Believe me, you I would remember!”

The man was still in the saddle, outlined in silhouette against the sky. “You were just twelve, the last time I passed through Esketh. You were in school. I stayed a week, but you weren’t home. I saw you playing ball with your friends, but you never bothered to notice me.”

“You were at Roald’s house?” Martin was astonished, and searched his memory, trying to recall where he would have been that summer, eight years ago. It must have been one of the months he stayed on at the school, because he wanted to play ball, and study with some of the visiting tutors — and just to get out of Roald’s house for a while and feel like a freeman. Roald had always told him he was family, but —

“Your guardian made me welcome,” Leon was saying. “He always does.”

“Always?” Martin heard the sharp tone in his own voice. “But I never saw you before.”

Leon only shrugged as he swung down to the ground and set about pulling the big saddle off the horse. “I don’t come through as often as I should. Eight years is a long time … too long. I haven’t seen Roald in a year, and we met by chance in the port of Krestway.” He rested the saddle on the bottom step, pulled a cloth out of one of the bags, and began to rub down the horse as he spoke. “This time I showed my face at Roald’s gate, it was all fear and weeping, and ‘Leon, will you do an old friend a favor? He’s gone.’ And I ask, ‘Who’s gone?” And Roald tells me it’s his moronic little whelp of a ward who’s taken off into the badlands — breaking curfew behind him, risking his stupid little life, and no one even knows what for, because in his wisdom, young Martin doesn’t even care to leave a note tacked to the door for Roald or Imara to find when they get home!”

It was all true, and Martin might have cringed. “If I’d told Roald where I was going,” he muttered defensively, “he’d have stopped me.”

“Of course he’d have stopped you!” Leon’s hands were quick and abrupt as he rubbed the horse’s flanks, betraying his anger. “It’s bandits and skinners out here, and it’s the sheriff for you in the morning, and the bastinado, unless Roald and I take responsibility for your stupidity!”

“Yes, but —” Martin began, and stopped. But what? Anything he could say was only going to make him sound more of a fool, and Leon already had a poor impression of him. Instead, he sealed his mouth and let Leon talk.

Done with the horse, he turned back toward Martin and stood in the moonlight, hands on hips. “It’ll be me taking responsibility, because Roald has to live here after I’ve moved on, and he’ll be disgraced. Word’ll soon get around that he can’t even control his own ward — the one who calls himself a man grown, but hasn’t done a day’s service in the militia to earn his right of majority!”

The militia had haunted Martin since he was old enough to understand how the system worked. Almost all of his friends had done their service; some had given their lives to Esketh, others were crippled — and every one of them had blood on his hands that would never wash away.

“The militia is sent to war,” he said quietly, wondering if a seasoned warrior would be able to understand a word he was saying. “I don’t want to kill anyone. And I — I don’t want to get killed myself.”

“No?” Leon’s brows knitted in a deep frown as he mulled over Martin’s words. “You don’t want to spill blood for the honor and defense of Esketh, but you’ll come out into the badlands after dark, and you’d have expected me to kill Yussan to save your skinny little neck.”

“He was going to sell me!” Martin protested. “He trades in captives and you — damnit, you know him!” He glared up at Leon. “Who is he?”

A wry half smile banished Leon’s frown. He reached up to take the bridle, lead the horse around into shelter. “Yussan? He’s my cousin.”

For a moment Martin was sure he had misheard. “Your — cousin?”

With a deep-throated chuckle Leon led the horse into the lee side of the cenotaph. He had set out feed and a pail of water there when he pitched camp, before going hunting. In a moment the horse was drinking, eating. “Don’t get excited. My parents had six siblings apiece. I have more than fifty cousins. Some are merchant princes and soldiers. A few are mercenaries like Yussan. Lucky for you, he’s one of the decent ones.”

“Decent?” Martin demanded.

“There’s an echo in here,” Leon observed.

“He was going to sell me!”

Leon leaned down, hefted the saddle. Halfway up the steps, he stopped, turned back. “Yussan deals in morons. I still haven’t heard a word about why you broke curfew and set up a killing field. If it had been anybody else but Yussan, I’d be cleaning my sword right now … and if he hadn’t backed off when he did, I’d have had to wound or kill my own flesh and blood. And you — you don’t seem to care!”

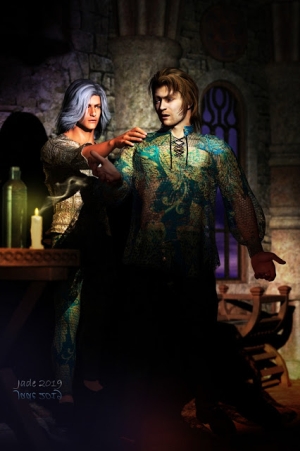

Without waiting for an answer, he turned away, marched up the stairs and began to unthong his saddlebags. Trailing after him, Martin saw that he had set up a rudimentary camp when he swung through here on the way out. A bedroll, a black pan, a pair of mugs, a pack of dried food, two skins of water, were all set on the side of a hearth that had been built by other campers, who knew how long ago.

“I had to come out here,” Martin muttered as he watched Leon fetch out an assortment of jerky, dried vegetables, flour, salt.

“Somebody made you break curfew, did they?” He spared a glance for Martin as he struck flint against steel in the hearth.

A little swatch of tinder caught alight at the tenth spark, and Martin watched him lean down to blow on it, bringing the fire alive. “Well, no,” he admitted, “but I was …” There was nothing for it but to tell the truth, and he gritted his teeth. He knelt by the hearth, intent on Leon’s hands as he said, “I was going to meet a man. A guide. He was going to take me into the hills to find — well, he’s supposed to know where there’s a tomb. And a relic, hidden in it.”

The fire was burning, crackling, when Leon straightened and looked down critically at Martin. Some of his wrath seemed to have diminished, and Martin was sure he heard a trace of wry humor as he observed — it was not a question — “You’ve been talking to the Gypsies.”

A wind out of the south caught Martin’s hair, tossing it into his face. If this had been daytime, it would have been a hot wind. “Why shouldn’t I talk to them?” he demanded. “You have something against Gypsies?”

The remark elicited another chuckle. Leon stooped to add kindling to the fire, and reached for the skins of water. “I am a Gypsy,” he said ruefully as he filled the black pan and hung it over the hearth. “I was born one of them, and I know every one of their ridiculous stories. Which one was this? The goldmine in the mountains? Or was it the treasure of great kings, buried in some lost cave?”

“No.” Martin heaved a sigh and looked up at Leon, wistful, embarrassed, annoyed with himself, and grieving a little, that another dream — perhaps a boyish dream — had perished. “I was talking to Miranda. You know Miranda?”

“I should. She’s my great aunt.” Leon looked out into the darkness as a jackal screamed somewhere, far away. “And she told you…?”

“She told me a story — a damned good one! Good enough to fool me. About a cryptic map that’ll get you to the gates of Atlantis. It’s, uh, not true, then?”

But Leon only shrugged with an eloquent twitch of the big shoulders. “It’s a legend. Some part of a legend is always true, or it wouldn’t have come to be a legend.”

“Well, that’s why I came here,” Martin sighed. “I need to … to make something of myself.” The last was a confession, and unexpectedly painful. He felt a sudden heat rise in his face that had nothing to do with the fire, which was burning brightly now.

For a long moment silence settled over the cenotaph. The loudest sound was the crackle of the hearth, the chirp of crickets, the cry of a hunting bird. At least Leon had not mocked him out of hand, Martin thought, and at length the warrior prompted, “I’m listening.”

“I … don’t want to do militia service,” Martin said slowly. “I’m not afraid to fight, but I don’t want to kill. If I let them send me to the militia, they’ll make me kill, and I … don’t want that. But if I don’t do militia service, I’ll never get my right of majority, will I?”

“No,” Leon said thoughtfully. “Not in Esketh. You’ll be able to work, and wed, and have children, but —”

“But I’ll never be able to own property or trade. You understand, don’t you?”

The water was starting to steam. Leon added sticks to the fire and vegetables and salt to the pot. “Oh, I understand more than you know. I understand Roald fostered you when your parents were killed when you were five years old … I understand that you owe him everything you have. You went to school. You’re educated, healthy, well fed … ambitious. I understand you don’t care if you just scared the wits out of him and put me in harm’s way to bring you back.” He stirred the pot with a blackened wooden spoon. “And if I’m going to keep Roald from being disgraced, it’s me who’ll answer to the sheriff for you tomorrow. If there's a fine to be paid, I'll pay it!”

Again Martin sighed, and had the grace to duck his head. “I didn’t mean any harm. I didn’t think.”

“Morons rarely do,” Leon said in philosophical tones. “For your information, the story as I heard it says the map leads to Lemuria, not Atlantis. And it’s not a treasure of gold or jewels there, it’s a magickal papyrus so old, nobody knows where it came from. Speak its words to elder archons and daemons, and they’ll grand your heart’s desire in exchange for amusing them for an instant in the boring eternity of their lives.”

Martin’s heart leapt. “You know the story!”

“Oh, I know it.” Leon dropped down to sit on the bricks at the side of the cenotaph. “And from what I can see, you’re an ungrateful whelp. Roald put me under oath to tan the price of this out of you … if I ever caught up with you before you vanished into a trading caravan heading over the mountains for Arkeshan and beyond. Well, I found you. And I’m still waiting to hear one syllable of remorse. All I’m hearing is excuses.”

A rebellious nerve came alive in Martin. He sat on the cracked old marble flagstones, leaned on one palm and looked into the fire. “I have to make something of myself. Roald has four kids now. I’m the adopted one — the outsider. He’s good to me, but the others are his pride. All I have ahead of me is work, militia, soldiering. So I talked to the Gypsies. Miranda told me the story, and I came here to meet a guide. It’s not an excuse, it’s the truth. What more could I tell you?”

“You could be contrite,” Leon suggested. “You might regret what you’ve done, or have a little gratitude for Roald — even for me. Do you feel any of that, boy?”

“Well … I am sorry,” Martin said honestly, though he was reluctant to say the words aloud.

“I wonder,” Leon mused. “I really wonder if you are. The sheriff would flay the flesh off your soles, and do it with great joy, for this trouble you’ve made. Now, tell me. What am I going to do?”

“You could accept my apology,” Martin said too quickly.

Leon’s dark head cocked at him. “If I thought it was genuine, I would,” he admitted. “But I don’t.”

“Then …” A pulse drummed in Martin’s throat. “Accept that I had my reasons, and … I’m an idiot, and didn’t think about what I was doing. Just followed my nose. And my heart.”

The suggestion did little to convince Leon. “You followed your ambition out here. That’s an explanation, not an apology. I understand why you’re here, even though I can’t forgive it any more than the sheriff could. Or Roald,” he added pointedly.

With a smooth movement, lithe as a cat, Leon stood. “Damned right, you won’t. It’s remorse I wanted to hear, and I’m not hearing it. So you can hand me that wrap and get over here. I understand what you’ve said — and I also understand a young man’s pride. But there’s only one way you’re going to learn, only one way you won’t go to the sheriff in the morning.” And he held out his hand to take the wrap Martin wore around his hips.

“You — you wouldn’t,” Martin stammered. “You could tell them you tanned me.”

“But it would be a lie.” Leon was waiting. “Roald would know at a glance. Not good enough, Martin. Now, get over here and think about the pain you’ve caused Roald, the hazard you’ve put me in, the trouble with the sheriff, if we’re going to prevent Roald being disgraced!”

And with that, Leon sat back down on the low wall and patted his lap. His hand was still extended to take the soft leather of the wrap, and with a quiet gulp, Martin slipped it off and passed it to him. Leon set it aside and patted his knee again.

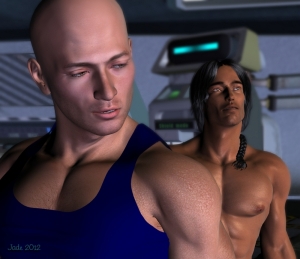

His voice was level, his face thoughtful. Firelight danced around his features, sparkling in his eyes, turning his skin to molten gold. Martin had never seen anything quite like him — born a Gypsy, was he? — and his heart battered his ribs as Leon said,

“I’ll take into account everything you’ve said … and if you make me wait much longer, I’ll take cowardice into account as well. You don’t want to keep me waiting. Look inside, seek honest, genuine remorse. It’s hiding in there.”

Dry mouthed, Martin took his courage in both hands and clumsily, awkwardly, draped himself over the warrior’s knee. He tried to find his balance there, tried to take his weight on his palms. He was still off balance when the first blow fell, and he gasped in a breath. Leon’s palm was like leather, and his arm was as strong as a blacksmith’s. He could swing a sword all day on the battlefield, and that strength slammed into Martin where he was softest.

It was the first time he had ever been struck. Roald had never disciplined him with anything stronger than a sharp word, and Imara had treated him as her eldest son, with every care —

The second blow was as hard as the first, and the third set up a rhythm that seemed easy for Leon while Martin’s breath had begun to pant. “You’ve never done militia service,” Leon said slowly, pacing words and blows, “nor felt a birch rod on your back. If you get your way, you’ll never wear the militia badge or carry a set of stripes because some bastard sergeant took a dislike to you, used you to set an example to others your age. Lads with the same irresponsibility that has Roald in tears tonight — and his reputation hanging by a thread. You think the sheriff will favor him in a dispute after this, if he can’t keep his own ward in order?”

The phrases were punctuated by wallops that brought tears to Martin’s eyes — but there was more. He knew from Leon’s voice, he had felt the bite of the birch, borne the brunt of a sergeant’s dislike. His fierce protection of Roald spoke clearly to Martin.

Only love made a man risk his life the way Leon had done. Whatever he and Roald had shared was beyond anything Martin knew. Would Leon have killed his cousin for the sake of Roald’s ward? Yussan could be dead now, by Leon’s sword — all this swam among Martin’s ragged thoughts as the leathery palm continued its rhythm. Pain stormed through him as Leon said,

“Damn! A year in service in a town fifty miles up the spice road would teach you how to respect your home and your kin, and do right by them! They’d soon teach you the value of compassion, respect, kindness!”

Perhaps pain opened his eyes to the truth; maybe it was something like one of the ancient purification rituals that were said to make a man see clearer. For the first time in his life, Martin was aware of his own ignorance and self-centered behavior. For the first time in his memory, he saw from someone else’s perspective. The remorse Leon was looking for smarted him much more sharply than the warrior’s leathery hand.

It was the remorse, not pain, that made him sag over Leon’s knee in surrender, and it seemed this was what Leon had been waiting for. He knew to the instant when Martin woke up to what he had done. Four more wallops fell — harder than those before, but they were the last.

Then Leon took him between strong hands and physically turned him over, but Martin could not look at him, much less meet his eyes. He would almost prefer to be tanned again than feel this remorse. He hid his face in Leon’s shoulder and wondered how he was ever going to look Roald in the face.

Leon held him, and Martin’s heart beat like a hammer with genuine contrition; and with more. Leon’s strength and body heat were sheer heaven. His embrace was a safe haven. Martin moved closer, wanting more. He knew he ought to be hanging his head in shame.

“Tell Roald,” he said, muffled. “I didn’t think. I didn’t mean it to go like this. It just happened.”

“Things turn out the way they turn out,” Leon said thoughtfully, hands on his back. “And when they go askew, sometimes it comes to blood. I’ll tell Roald … but one glance at you, and he’ll know. He won’t need me to say one word.”

“Will he forgive?” Martin shuffled around, trying to find comfort. “You surely know him better than I ever did. Will Roald forgive?”

For a moment Leon studied him, touched his hair, brushed it back from his face. “The Roald I always knew wouldn’t have to, because he wouldn’t accuse. The flat of my hand? Much easier than the bastinado or a birch cane, believe me, and you could have suffered either one, since you’ve become a man. But the sheriff will be appeased, too.”

“You’ll tell him?” Martin insisted.

“I’ll speak for you. We won’t involve Roald.” Leon’s right hand cupped the back of Martin’s head, and he looked long into Martin’s eyes.

“Yussan would have sold me, wouldn’t he?” No doubt of it, now, in Martin’s mind.

“Trained for a fine house,” Leon affirmed, “then sold to someone who couldn’t afford you, and so would have treated you like glass. You’ve the beauty for it.” His fingertips traced Martin’s mouth. “Do you know how many fugitives perish out here? The truth is, service on the spice road has saved many lives! Don’t think too ill of my cousin. He has his own code, and he holds to it.”

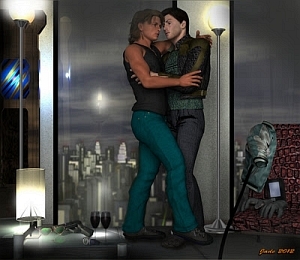

And then Leon leaned forward across the small space that separated them, and laid his mouth on Martin’s.

It was not Martin’s first kiss, but it might have been. It was the first time he had been in the arms of a warrior, and a warrior’s kiss was little like the kisses of tavern wenches and the lads with whom he took class; and it told him better than words, Leon counted the debt settled. Yussan would find other merchandise; the sheriff would be appeased, Roald’s name would not be sullied … and Martin?

What of Martin?

Nothing was the same now. He could barely catch his breath, could not take his eyes from Leon’s lean, angular face, and could not make sense of the words as Leon spoke to him.

“Eat,” Leon was saying as he added jerky to the pot, and stirred in a little flour to thicken the broth. “Get something hot into you, and then get some sleep. It’s going to be another rough day tomorrow.”

Sleep? Martin’s whole body was alive, from the haunches that were sore to the heart that was still hammering, for different reasons. “Sleep? But —”

“I said, sleep,” Leon insisted. “I’m going to, just as soon as I’ve eaten!”

Martin’s head was spinning. He should have been hungry, but as he took a mug of food from Leon he knew he would have to force himself to eat. With a flash of insight he knew what he wanted, and it was far from what he had thought he wanted when he came out to these badlands.

Carefully, uncomfortably, he settled, fathoming a way to rest. He ate a little, set the rest aside for morning, and closed his eyes. He had not expected to sleep, but the day had been a year long and odd, dislocated dreams seemed to ambush him.

NOTE: The Abraxas Contents List link is in the left-side column -- quick links to each chapter

*********************************************

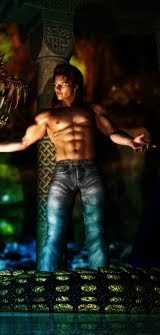

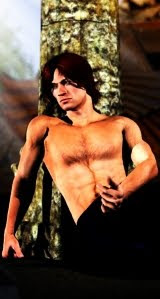

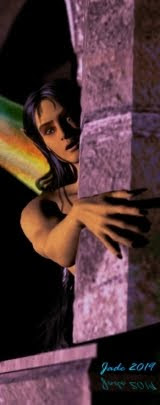

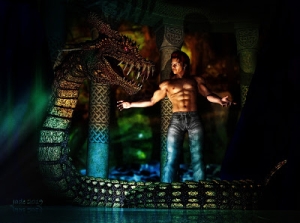

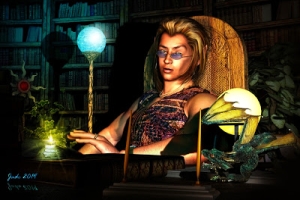

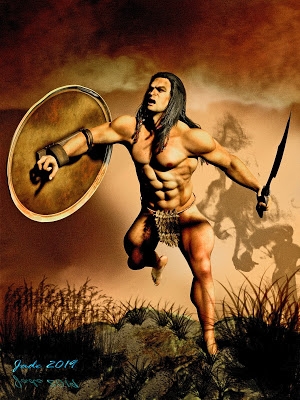

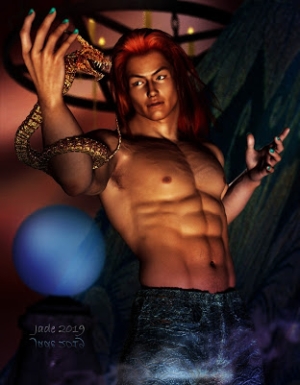

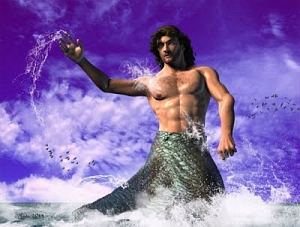

And there, I'll leave the story till next time. This took longer than I'd expected ... personal reasons, added to which, it's a lot longer than some of the other segments! The art also wasn't quick: there's a whale of a lot of painting on this piece ... and it shows!I It's really interesting, taking the original web comic and transposing it into a novel. This brings us up to page 45 or so, and in narrative form, it's about 10,500 words. I had no idea it would expand this way ... looks like it's going to be a whole novel, when finished. More soon!

With a little bit of luck, I'll be back tomorrow with the "Microcosm" feature I promised. The world of the very small ... the forest floor, a series of images from a shoot I did over three years ago, and lost. Actually, I didn't lose them, just misfiled them somewhere among four terabytes of storage space. The whole project literally vanished, and -- isn't it always the same? You tear the house apart looking for "this," and find "that" instead. Serendipity: a happy accident.

Jade, September 29

NOTE: The Abraxas Contents List link is in the left-side column -- quick links to each chapter

*********************************************

And there, I'll leave the story till next time. This took longer than I'd expected ... personal reasons, added to which, it's a lot longer than some of the other segments! The art also wasn't quick: there's a whale of a lot of painting on this piece ... and it shows!I It's really interesting, taking the original web comic and transposing it into a novel. This brings us up to page 45 or so, and in narrative form, it's about 10,500 words. I had no idea it would expand this way ... looks like it's going to be a whole novel, when finished. More soon!

With a little bit of luck, I'll be back tomorrow with the "Microcosm" feature I promised. The world of the very small ... the forest floor, a series of images from a shoot I did over three years ago, and lost. Actually, I didn't lose them, just misfiled them somewhere among four terabytes of storage space. The whole project literally vanished, and -- isn't it always the same? You tear the house apart looking for "this," and find "that" instead. Serendipity: a happy accident.

Jade, September 29